.

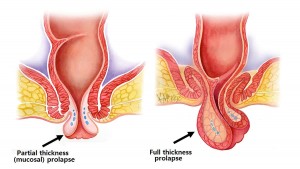

Rectal prolapse describes a condition where either the lining or entire wall of the rectum becomes loose and falls into, or even out of, the rectum through the anus.

Types of rectal prolapse

There are two types of rectal prolapse:

- Partial thickness prolapse (also called internal intussusception).

- Full-thickness prolapse (also called external prolapse).

Partial-thickness rectal prolapse

Partial thickness rectal prolapse, is where the lining of the rectum (mucosa) becomes loose and falls downs into the lumen of the anal canal when straining. Because it is not full thickness, it rarely prolapses enough to protrude through the anus. Partial thickness prolapse may cause some degree of blockage in the rectum when straining (obstructive defecation), and may be a contributing factor to constipation. It can also lead to a feeling of incomplete evacuation.

Full-thickness rectal prolapse

Full thickness rectal prolapse is where the entire wall of the rectum becomes so loose that on straining it telescopes on itself to such an extent that it falls out being visible external to the anus. Full thickness rectal prolapse is often mistaken for a haemorrhoid, as bleeding and mucous discharge are common symptoms.

Cause

Rectal prolapse is caused by weakening of the muscular pelvic floor and ligaments that support the rectum keeping it in place. Rectal prolapse may be associated with advanced age, weight loss, long term constipation, long term straining during defecation, previous pregnancy or obstetric trauma and multiple childbirths. Frequently in women rectal prolapse is also associated with a rectocele. which is a weakness in the rectal wall where it balloons into the vagina.

Symptoms

The commonest symptom of rectal prolapse is mucous discharge from the anus or occasional bleeding. The prolapse may be noticed as bulging mucosa typically on straining. Rectal prolapse may give the sensation of constipation (obstructive defecation) or incomplete emptying when having a bowel motion.

Investigation

Full thickness prolapse is clearly evident with bearing down with eversion of the rectum and a protruding bulge. Therefore, this diagnosis is made clinically. Partial thickness (mucosal) prolapse can sometimes also be severe enough to result in prolapsing mucosa that bulges and is visible external to the anal sphincter on straining (Figure 1a). More typically however, it is less obvious, and is visible on defecating proctogram, a real time x-ray taken while defecating. Rectal prolapse may also be more obvious in the relaxed state, such as under general anaesthesia.

Colonoscopy

All patients with rectal prolapse and symptoms of constipation or incomplete evacuation, require a complete colonoscopy to rule out other pathology of the colon that can result in these symptoms.

Defecating proctography

Defecating proctography is useful for documenting partial thickness rectal prolapse causing obstructive defecation.

Transit studies

Those with constipation as the major feature without obvious full-thickness external prolapse, should have transit studies to exclude slow transit constipation prior to surgery.

Prevention

There is little that can be done to prevent rectal prolapse. Any procedure or condition that weakens the pelvic floor (e.g. childbirth or obstetric trauma), increases the risk of rectal prolapse later in life.

Course

Mild rectal prolapse, may progress and become more advanced with time. Partial thickness prolapse can in some cases progress to full thickness prolapse. Typically prolapse occurs during straining when having a bowel movement, or when sneezing or coughing. As it develops, it occurs more frequently, even throughout daily activities such as walking. Finally, it may be prolapsed continually, and in the worse form, ceases to retract being irreducible.

Medical management

The constipating effects of partial thickness rectal prolapse may be treated by a diet high in fibre and regular laxatives. This leads to less firm stools and the avoidance of straining. A sanitary pad is often required to deal with the mucous discharge and bleeding.

Surgical management

The alternative is surgery. Surgery is generally of two types:

- Endoscopic surgery

- Open surgery (perineal and abdominal approaches).

Endoscopic surgery

For partial thickness, internal mucosal prolapse, endoscopic mucopexy may be an option. This does not involved any cutting. In this procedure an anchoring suture is used to fix the inner rectal lining to the rectal wall. The redundant prolapsing mucosal is the stitched and lifted back up to this anchoring stitch.

Open Surgery

Open surgical options include those via the perineum, and those via the abdomen.

Perineal surgery is where the surgery is performed on the rectum approached from the anus. It does not involve major abdominal surgery, and is particularly suited in the elderly and those with multiple medical conditions that would make abdominal surgery unsafe. Perineal procedures include those that deal only with partial thickness prolapse (STARR procedure, or stapled mucopexy), and those that deal with full thickness rectal prolapse (Delorme’s and Altimeier’s procedure)

Abdominal surgery involves mobilising the rectum, and suspending it, usually with mesh, to the bony prominence (sacral promontory) of the pelvis. Abdominal surgery for rectal prolapse is increasing being performed key hole (laparoscopic or robotically) with benefits of small incisions and less pain than traditional open surgery. Robotic ventral mesh rectopexy has the benefit of allowing magnified vision and more precise suturing due to miniature robotic hands inserted within the abdomen.

Patients with rectal prolapse without constipation as a major feature will benefit from a mesh rectopexy. Patients with rectal prolapse with constipation as a major feature may benefit from a slow transit study to rule out slow transit constipation. For those with constipation, resection rectopexy, where a portion of the redundant bowel is removed, may be preferable to mesh rectopexy, although the added risk of 1-2% of anastomotic leak is the major down-side of resection rectopexy.

What to expect prior to surgery for rectal prolapse

Clear Fluids

You will need to have only clear fluids the day before your surgery. Clear liquids are those that one can see through. When a clear liquid is in a container such as a bowl or glass, the container is visible through the substance. Examples of clear fluids include water, broth, apple juice, jelly, sports drinks such as Gatorade®, Lucozade® and Gastrolyte®. Try to drink at least 3-4 litres the day prior to your surgery.

Bowel Preparation

You will also require bowel prep to clean your colon. Take a Pico-sulfate (Picolax®) sachet (mixed in a glass of water) at 2pm, 4pm and 6pm the day before your procedure. If you are prone to constipation, the 4pm Picolax is replaced with a sachet of Glycoprep (mixed to a litre with water). You can purchase these from your chemist without needing a prescription.

Nil By Mouth

You need to be nil by mouth (i.e. no liquids) from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 6am if scheduled for the afternoon.

Admission Time

The exact time for your admission is finalised the day prior and you will receive a phone call in the morning at about 10am to inform you what time to present. This is normally 2 hours prior to the planned start time.

What to expect after endoscopic surgery for rectal prolapse?

Diet

Immediately after your procedure you will be commenced on a light diet.

Pain Relief

You will be given a Patient Controlled Analgesia (PCA) device to administer your own pain relief for the first 24 hours, then this will be replaced with oral pain killers, usually paracetamol, and a nonsteroidal such as Celcoxib® or Nurofen®, and if needed oral oxycodone (oxycontin®).

Laxatives

You will be on regular laxatives (Movicol®) from day 1, and should remain on this for 6 weeks. The dosage is individualised, with huge variation between patients. The usual starting dose is one Movicol® twice daily. This can be halved or doubled or quadrupled depending on the response. The aim is soft stool to avoid straining.

Exercise

Walking is encouraged from day one, as this improves your recovery and prevents against developing a venous clot and pneumonia. Gentle swimming or cross-trainer or cycling can occur after 48 hours. No vigorous running, jumping or exercises are recommended for 6 weeks after surgery.

Discharge Home

Usually you will be discharged from hospital the same day, although sometimes overnight admission is required for pain relief, or if urinary voiding is an issue.

Regular medications

If not already done so, you are to go back on all your regular medications on discharge.

Follow-Up

Please ring 1300 265 666 to organise a follow-up appointment with your surgeon at 2-6 weeks after your procedure.